Architectural and Landscape History

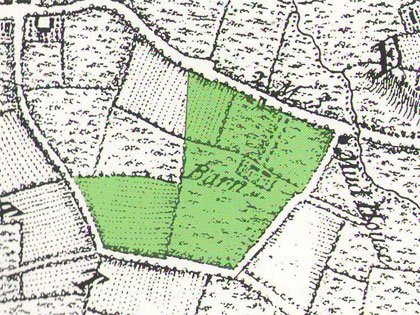

When Edward Loveden Loveden decided to build Buscot Park, he chose a local prominence, then called Farnhill, or Farn Hill, for the site of his new mansion. This land lay outside the historic Loveden estate, forming part of the adjacent Throckmorton estate. Loveden paid the existing tenant a premium in order to acquire the lease. The hill, to the east of Buscot village, commanded northward views to the Lechlade-Faringdon turnpike and to the flat lands beyond the Thames. John Rocque's map of around 1760 shows a barn and an avenue close to the site; both were removed when adjacent farmland and heathland were enclosed to create the first park and garden.

The design of the house was once attributed to Loveden himself, but it is now known that he also employed James Darley (1744-1821) to build the mansion and main phase of the park. Darley, of Hullavington, in Wiltshire, was described in his own day as 'an able and experienced architect', and had previously been employed as clerk of works at Charlton House, near Malmesbury, during alterations carried out for the Earl of Suffolk in 1772-6.

Another possibility is that Buscot was designed by William Newton (1735-90), a London architect who, like Loveden, was a Fellow of the Society of Antiquaries. Newton published the first English translation of the works of the ancient Roman architect, Vitruvius, and so was steeped in the neo-classical style. His papers include reference to a drawing that he exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1780 of a house 'now building in Berkshire', which could well be Buscot Park, though the drawings themselves have not survived. Adam and Wyatt have also been cited in the past as having had a hand in the design, but no reference to any of the four possible architects has been found in the building accounts.

The one architect how is mentioned in the accounts is James Paine Junior, who was employed in 1782 to assess the cost of the work completed so far, and who supplied chimney-pieces worth £105 in 1783. As the only professional architect mentioned in the accounts, Paine cannot be ignored, and though his other designs are quite unlike Buscot Park, it is possible that he was responsible for the interiors.

No matter who designed the house, the architectural historian Christopher Hussey wrote in 1940 that:

'The designer of Buscot displayed excellent taste and no little skill in the management of his proportions and his choice of detail. He owed much to Adam, obviously, and perhaps to the pattern-books and moulds of the admirable tradesmen of the day. But the plan of the house is conventional, with its hall and saloon in the centre of either facade and transverse corridor, deriving rather from earlier, Palladian, tradition. As was frequent in the Age of Landscape, the principal rooms are on a piano nobile approached by the broad steps to the front door and from the windows of which a prospect is enjoyed over the surrounding countryside.'

Begun in 1780, the house was built by local craftsmen using local materials, but with mahogany doors, Westmorland slates and block steps and landings of Portland stone, all acquired from a sale by Darley's former employer at Charlton House. Stones, lead and further slates were also bought from Kempsford House, in Gloucestershire. Roofing began in October 1781, and an early view of the new house, painted by Joseph Farington, RA, was engraved by J.C. Stadler and published in June 1793. This shows the double flight of stone steps, centred on the nine-bay south front, with its pedimented three-bay centre and the seven-windowed orangery to the east of the mansion. To the west, at the foot of Farn Hill, are the approach road and the turnpike lodge. Further west, the clock tower, with its turret clock and cupola, is visible, rising from the roof of the courtyard stable block. This, along with the adjoining kitchen garden - broadly oval with an outer wall of brick and an octagonal inner core - was built during 1781, along with the mansion works. Fruit-tree planting is recorded in the autumn of 1782.

The Park

Parkland work commenced in earnest as the mansion works were nearing completion in 1782. Park paling was completed during the summer of 1782, when deer were bought. Underground drainage was carried out in the spring of 1782, followed by the digging of the fishpond in the summer, and tree planting in the autumn. The sward was sown in the spring of 1783. These initial works comprised 120 acres of parkland pasture, 5 acres of water, 23 acres of plantation and 5 acres of kitchen garden, plus one acre of shrubbery around the house. The layout made the best use of the local topography, and its simple arrangement created a setting for the mansion that echoed the English Landscape fashion of the period.

Between 1786 and 1792, Loveden spent the considerable sum of £60,000 in order to expand the estate by purchasing numerous local landholdings. In 1788 he acquired the neighbouring Throckmorton estate, and so became the owner of the Farn Hill land on which his house was built, and by 1798 he owned most of Buscot parish, as well as parts of Eaton Hastings, Coxwell and Faringdon. To the east of the house he created a new 20-acre lake fed by an existing stream; to the west he extended the deer park and to the south he took more heathland and pasture into the park, adding a further 107 acres overall. The lake was a particular feature, creating long views across the water from the north front of the house to an eye-catching bridge that closed the eastern end of the lake.

The Estate Matures

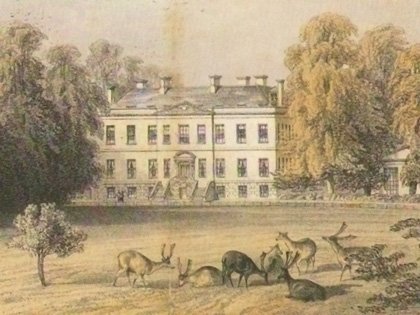

J.S.Kell’s mid-nineteenth-century lithograph of Buscot Park shows the mansion in its mature setting some seventy years after its completion. Further changes and additions were prevented by financial constraints and Robert Campbell, the new owner from 1859, seems to have cared more for his experiments in the industrialisation of the estate than in changing the design. A number of anonymous and finely executed sketches have been found, some dated August 1859, which indicate that Campbell was toying with various ideas for reworking the mansion, deploying an eclectic mix of Italianate towers, mixed with Gothic and Elizabethan windows.

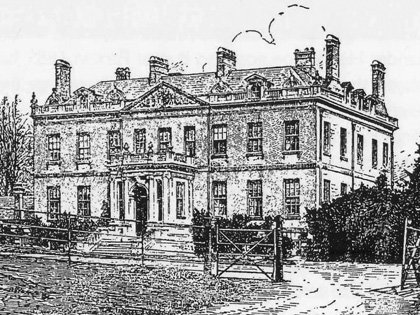

In the event, Campbell’s enhancements to the house were far more modest, consisting of a new porch and flight of steps to the south front, and the addition of gabled dormers and balustrading to the eighteenth-century parapet. The orangery was demolished in order to create Italianate terraced gardens to the east and north of the house, with broad paths and geometrically shaped lawns, supported by bastion walls, and embankments. A new approach to the house was created by laying out a new carriage drive from the south front of the house leading eastwards through woodland and offering fleeting glimpses both of the house and of the lake.

Harold Peto & Ernest George

Campbell’s improvements to the park and gardens, along with his creation of a number of boundary plantations and his opening up of various vistas, laid the foundation for the most exciting phase in the garden’s development. When Alexander Henderson acquired Buscot Park in 1889, he employed the Ernest George Partnership to enlarge the mansion and build various cottages, farm and public buildings in Buscot village. It was through Ernest George that the renowned landscape architect, Harold Peto, was then invited to Buscot to work on improving the links between the house and the lake.

Peto was a former partner of Ernest George, leaving in the early 1890s to establish what subsequently developed into a substantial garden design practice. Peto worked much in the Mediterranean and was a leading exponent of the revived principles of Renaissance garden design, as well as an avid collector of antique, Gothic and Renaissance architectural fragments. At Buscot Peto laid out the renowned water garden between the north-front terraces and the lake. He also added a new forecourt to the south front of the mansion, adding balustraded walls and stone gate-piers. Next to the forecourt he planted a semi-circular sweep of yew hedging to contain the figure of Diana returning from the Chase, which he had purchased in Rome.

Geddes Hyslop

Ironically, the 2nd Lord Faringdon’s first action on inheriting Buscot in 1934 was to remove his predecessors’ additions, including Campbell’s elaborate porch and balustrade and the 1st Lord Faringdon’s large west wing, which marred the restrained lines of the original Darley and Loveden design. His architect was Geddes Hyslop, who designed, at the same time, the two balancing pavilions that now stand west and east of the house.

Today the main elevation is much as it must have appeared in 1780. The severity of the composition is relieved by the slight projection of the three central bays, which support a pediment enriched with a flowing foliage design and bearing the Faringdon crest. A broad flight of steps, flanked by bronze centaurs after the antique originals in the Capitoline Museum, gives access to the house on the piano nobile.

To the south, Hyslop introduced the wrought-iron screen and stone gate-piers on a ha-ha wall and linked the south-front lawn to the kitchen garden by creating a hedged flight of steps, centred on the pond at the centre of the walled garden. The north-front lawn was linked to the Peto water garden by semi-circular stone steps, and a radiating patte d’oie (goose-foot) of avenues and garden enclosures was laid out to the south of the Peto garden, aligned on the mansion.

Recent Garden Works

The gardens and grounds have continued to evolve under the present Lord Faringdon. As well as adding a fountain to the north-front pool and a new avenue to the south east of the mansion as part of the twentieth-century garden circuit, he has been most active within the walls of the eighteenth-century kitchen garden. New works have included the richly planted borders in the former melon garden, designed by the late Peter Coats, and the Four Seasons garden, laid out within the octagonal garden walls

= House & Grounds Open

= House & Grounds Open = Grounds Open Only

= Grounds Open Only = Closed

= Closed

>

>